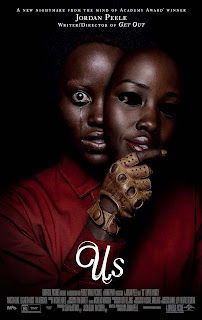

Us and Woke Ableism

(spoilers ahead for Us and Get Out)

(content warning: lots of ableism, generational trauma, collective trauma, sexual assault, ableist slurs used in song titles, police brutality, government-mandated genocide)

Foreword: I Actually Liked Us

Don't take this the wrong way.

Jordan Peele is one of the greatest directors working in Hollywood right now. His first two films as director, 2017's Get Out and 2019's Us, are bold statements on how we view American togetherness and, by proxy, the unwavering nature of the American Dream. Get Out tackles the issue of race - in particular, the cynical-but-seemingly-well-meaning efforts of white liberals to endear themselves to the black community (whilst alienating them elevenfold) AND how the police seem to ignore black victims because of course - whereas Us seems to tackle everything about America. Us tackles our collective skeletons in the closet - from how we use charity as a mask to shield ourselves from all the really horrible things we've done to how our real selves often clash with our ideal selves to how the rich seem to control the poor at all times. Not only is that a really effective story - a bleak story about the little gray areas in our own lives as Americans, about how we're all complicit in our own horror stories - it creates for some of the most effective images seen in modern horror, helping create one of the best climates for genre film since the 1980s.

Lupita Nyong'o delivers probably her best performance yet - as PTSD-stricken mother Adelaide Wilson, still reeling from her own childhood trauma from when she got lost at the Santa Cruz Pier in 1986. She's pretty peculiar, from picking the seeds from strawberries to not really being open to why she's so hesitant upon returning to Santa Cruz for the summer, but nothing exactly out of the ordinary. Her character is simultaneously a great portrait of somebody trying to adapt to their trauma and somebody who's letting on more than they want you to know - realistic and mysterious, in layman's terms. As with everybody else in the film, Nyong'o also plays Adelaide's doppelganger Red, who seems to have a bone to pick with Adelaide's existence. And as you can see just on first glance alone, Red is the only doppelganger who can actually speak the language of Adelaide and her family. Everybody just grunts or screeches like a man-child begging for Zaxby's chicken tenders tossed in Insane sauce - that should tip you off from the get-go that there's something about Red. Something that makes her more sympathetic.

Set pieces intermingle humor, horror, and suspense, often within the same story beat. Take for example a fight between Gabe (Winston Duke) and his doppelganger Abraham on a rickety fishing boat. It's funny in how Gabe seems to find himself at the behest of Abraham's ploys to take over his life - but it's also scary in that this guy who came out of nowhere, who looks like Gabe to a T but can only scream like he were a feral child, is trying to kill this seemingly innocent man just to take over his life. Gabe makes sarcastic comments all throughout the battle, but he has to fight this seemingly malevolent personality while making these sarcastic comments. It is dark humor at probably one of its darkest points - about as dark as Get Out having Stephen Root's art dealer (who is literally blind) agree to the idea of him having his brain transplanted into Chris' body because he just wants his eyes (and therefore his talent). And that's a pointed commentary on how just merely taking somebody's aesthetic and running with it without taking their je ne sais quoi or the creator's own life experiences cheapens their talents and thus their contributions to the art form as a whole. Here comes Jordan Peele showing a struggle between a man's ideal and real self on a boat to show us how these battles aren't just clean-cut.

Hell, most of the battles in Us aren't clean-cut. The doppelgangers often exhibit striking moments of humanity - like Dahlia (Elizabeth Moss), the doppelganger of Gabe and Adelaide's friend Kitty, screaming in the mirror as if she's undergone this extreme trauma while also taking on elements of Kitty's own life (like putting on lipstick and trying to kill herself - as if she's not this inhuman clone that only serves to take over Kitty's life and is discovering how complex the human experience is for the first time). This only serves to enhance one of the many, many twists in the film - where the doppelgangers turn out to be millions upon millions of revolutionaries, all dubbed Americans by leader Red, who have been controlling the lives of Americans for YEARS at the behest of unseen forces and strive to see what the outside world is. These doppelgangers are giving to us what we collectively have deserved for years, be it our many genocides of people who don't fit the American ideal or our commodification of pressing issues into trendy charities like Hands Across America or how we've managed to white-wash the complex decade of the 1980s into Spielberg references and Michael Jackson because it's easier to sell nostalgia on its high moments than on its low points. For example, you don't want to see Mike and Jane experience the Iran-Contra Scandal as it actually happened. No, you wanna see them discover that Dr. Brenner's selling weapons to the Contras so he can build more portals to the Upside Down so that they can get down to the nitty-gritty of this mystery. Reality is seen as too boring. That's why genre films often use fantasy and allegorical-fictional elements to comment on our society - so people understand that, yes, this might be the total extreme of what's happening, but doesn't it say something that there are disadvantaged doppelgangers forced to lead people into their own lives while forced to subsist on lab rabbits trying to get revenge for the crimes that the people who live above ground do to them? Doesn't that say something that the normal people are seen as the bad guys by the Tethered?

Genre film has this talent for exposing the falsities in our own realities - showing us the reality of our surroundings, to quote Angelo Moore of Fishbone, through painting a fantastic picture that directly relates to our life. We ignore the news - television is a cold medium. We need all our attention to focus on it, but because it's such a passive medium, we don't focus on it that much - and if we do focus on it, we have to treat it like hot media, which is downright difficult if not impossible to do. But film - film is a hot medium. Film tells us the truth as long as the filmmaker knows what they're saying is true. Hell, Leni Riefenstahl and D.W. Griffith have used the medium to espouse some of the most monstrous ideas disseminated in the 20th century - because it's that effective. Through film of any genre, even "genre films" like fantasy, horror, science fiction, and comedy, you can communicate complex ideas that will be understood by everybody almost immediately. You focus all your attention on the film you're watching - so, for example, you'll understand the little nuances, from good to bad to poorly-aged, of Alvy and Annie's year-long relationship in Annie Hall, whereas a television interview with somebody like Hannah Gadsby who doesn't appreciate Woody Allen's monopoly on comedy and has to explain why she's not too keen on how he uses his complex films to shield himself from what he's truly done will shut somebody out based on their receptiveness to cold media.

Us explains this disconnect between hot and cold media as well through how different the reality is from the ideal. The doppelgangers aren't what they seem. Red is not what she seems. Adelaide is not what she seems. The funhouse is not what it seems - not just in its hasty rebadging from its "cool Native American mysticism" racism to cliched Arthurian lore, but in how it's the conduit by which the Tethered are housed in. The kids are not what they seem to be. Hell, the cliches are not what they seem to be. And the media that everybody consumes - from Adelaide's Michael Jackson prize shirt to how Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) seems to be listening to music all the time to Gabe's seeming pride in his alma mater (always wearing that Howard University T-shirt) to the family singing along to "I Got 5 On It" and Gabe trying to water down the actual meaning of the song when Zora tells her brother Jason (Evan Alex) that it's about drug dealing to the repeated use of Hands Across America - is not what it seems to be. Now why are all of those symbols being used?

This is where things take a dark, dark turn. And not in a good way either. Genius, but not in a productive way.

Lupita Nyong'o delivers probably her best performance yet - as PTSD-stricken mother Adelaide Wilson, still reeling from her own childhood trauma from when she got lost at the Santa Cruz Pier in 1986. She's pretty peculiar, from picking the seeds from strawberries to not really being open to why she's so hesitant upon returning to Santa Cruz for the summer, but nothing exactly out of the ordinary. Her character is simultaneously a great portrait of somebody trying to adapt to their trauma and somebody who's letting on more than they want you to know - realistic and mysterious, in layman's terms. As with everybody else in the film, Nyong'o also plays Adelaide's doppelganger Red, who seems to have a bone to pick with Adelaide's existence. And as you can see just on first glance alone, Red is the only doppelganger who can actually speak the language of Adelaide and her family. Everybody just grunts or screeches like a man-child begging for Zaxby's chicken tenders tossed in Insane sauce - that should tip you off from the get-go that there's something about Red. Something that makes her more sympathetic.

Set pieces intermingle humor, horror, and suspense, often within the same story beat. Take for example a fight between Gabe (Winston Duke) and his doppelganger Abraham on a rickety fishing boat. It's funny in how Gabe seems to find himself at the behest of Abraham's ploys to take over his life - but it's also scary in that this guy who came out of nowhere, who looks like Gabe to a T but can only scream like he were a feral child, is trying to kill this seemingly innocent man just to take over his life. Gabe makes sarcastic comments all throughout the battle, but he has to fight this seemingly malevolent personality while making these sarcastic comments. It is dark humor at probably one of its darkest points - about as dark as Get Out having Stephen Root's art dealer (who is literally blind) agree to the idea of him having his brain transplanted into Chris' body because he just wants his eyes (and therefore his talent). And that's a pointed commentary on how just merely taking somebody's aesthetic and running with it without taking their je ne sais quoi or the creator's own life experiences cheapens their talents and thus their contributions to the art form as a whole. Here comes Jordan Peele showing a struggle between a man's ideal and real self on a boat to show us how these battles aren't just clean-cut.

Hell, most of the battles in Us aren't clean-cut. The doppelgangers often exhibit striking moments of humanity - like Dahlia (Elizabeth Moss), the doppelganger of Gabe and Adelaide's friend Kitty, screaming in the mirror as if she's undergone this extreme trauma while also taking on elements of Kitty's own life (like putting on lipstick and trying to kill herself - as if she's not this inhuman clone that only serves to take over Kitty's life and is discovering how complex the human experience is for the first time). This only serves to enhance one of the many, many twists in the film - where the doppelgangers turn out to be millions upon millions of revolutionaries, all dubbed Americans by leader Red, who have been controlling the lives of Americans for YEARS at the behest of unseen forces and strive to see what the outside world is. These doppelgangers are giving to us what we collectively have deserved for years, be it our many genocides of people who don't fit the American ideal or our commodification of pressing issues into trendy charities like Hands Across America or how we've managed to white-wash the complex decade of the 1980s into Spielberg references and Michael Jackson because it's easier to sell nostalgia on its high moments than on its low points. For example, you don't want to see Mike and Jane experience the Iran-Contra Scandal as it actually happened. No, you wanna see them discover that Dr. Brenner's selling weapons to the Contras so he can build more portals to the Upside Down so that they can get down to the nitty-gritty of this mystery. Reality is seen as too boring. That's why genre films often use fantasy and allegorical-fictional elements to comment on our society - so people understand that, yes, this might be the total extreme of what's happening, but doesn't it say something that there are disadvantaged doppelgangers forced to lead people into their own lives while forced to subsist on lab rabbits trying to get revenge for the crimes that the people who live above ground do to them? Doesn't that say something that the normal people are seen as the bad guys by the Tethered?

Genre film has this talent for exposing the falsities in our own realities - showing us the reality of our surroundings, to quote Angelo Moore of Fishbone, through painting a fantastic picture that directly relates to our life. We ignore the news - television is a cold medium. We need all our attention to focus on it, but because it's such a passive medium, we don't focus on it that much - and if we do focus on it, we have to treat it like hot media, which is downright difficult if not impossible to do. But film - film is a hot medium. Film tells us the truth as long as the filmmaker knows what they're saying is true. Hell, Leni Riefenstahl and D.W. Griffith have used the medium to espouse some of the most monstrous ideas disseminated in the 20th century - because it's that effective. Through film of any genre, even "genre films" like fantasy, horror, science fiction, and comedy, you can communicate complex ideas that will be understood by everybody almost immediately. You focus all your attention on the film you're watching - so, for example, you'll understand the little nuances, from good to bad to poorly-aged, of Alvy and Annie's year-long relationship in Annie Hall, whereas a television interview with somebody like Hannah Gadsby who doesn't appreciate Woody Allen's monopoly on comedy and has to explain why she's not too keen on how he uses his complex films to shield himself from what he's truly done will shut somebody out based on their receptiveness to cold media.

Us explains this disconnect between hot and cold media as well through how different the reality is from the ideal. The doppelgangers aren't what they seem. Red is not what she seems. Adelaide is not what she seems. The funhouse is not what it seems - not just in its hasty rebadging from its "cool Native American mysticism" racism to cliched Arthurian lore, but in how it's the conduit by which the Tethered are housed in. The kids are not what they seem to be. Hell, the cliches are not what they seem to be. And the media that everybody consumes - from Adelaide's Michael Jackson prize shirt to how Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) seems to be listening to music all the time to Gabe's seeming pride in his alma mater (always wearing that Howard University T-shirt) to the family singing along to "I Got 5 On It" and Gabe trying to water down the actual meaning of the song when Zora tells her brother Jason (Evan Alex) that it's about drug dealing to the repeated use of Hands Across America - is not what it seems to be. Now why are all of those symbols being used?

This is where things take a dark, dark turn. And not in a good way either. Genius, but not in a productive way.

Chapter One: What is Woke Ableism? How Does it Relate to the Devaluing of Abuse Victims?

If you don't want to know the ending of Us, stop reading now.

Please stop reading if you want to experience this movie for yourself. You got $10. You can go watch it during the matinee. You can put five on it if you live in a place that offers $5 Tuesday showings.

I'll stop here.

---

----

-----

------

So I'm assuming you've seen it or, at the very least, don't care about spoilers and just want to know how the movie ends.

"No, Adelaide. You are the demons."

Adelaide is the doppelganger of Red. During Adelaide's little funhouse excursion back in 1986, she met her doppelganger, who promptly KOs her, leaves her handcuffed to her bed in the underground, and resumes her life, taking on the character of somebody with intense trauma while secretly being proud of herself. Adelaide, now having to live the life of Red, starts taking on Red's movements underground, which works out for her since, because Red takes up dancing while pretending to be Adelaide, she finds God and thus her true calling: to lead an uprising of the Tethered towards those they have to puppeteer the lives of. It takes her years upon years of preparation, but she finally gets her chance - conveniently, when Red comes into Santa Cruz when with her family.

This is a really effective twist - about how we often don't know our real selves - but therein lies the tragedy: we relate so hard, via Peele's excellent conveyance of PTSD via Mike Gioulakis' superb cinematography (every frame can be exhibited in a museum, that's how great and unique this film looks) and Nyong'o's layered performance as Adelaide and Red, to Adelaide that when the twist reveals that her fear of coming back to Santa Cruz is mostly her afraid of facing the music of what she did to this innocent identical of herself, it cheapens her PTSD into merely something resembling guilt.

This is not good.

Let me tell ya about woke ableism.

Ableism is the systemic discrimination of disabled people, alongside the promotion of values that devalue people who openly identify as disabled in any way as either inspirationally disadvantaged (like blind musicians and autistic savants) or total screw-ups (like Christine Chandler or Timothy "Timbox" McKenzie) or total monsters (like any serial killer who only gets analysis because they have all of the mental illnesses). This isn't just relegated to lifelong mental and physical disabilities like autism or blindness either - victims of PTSD can often suffer from ableism. In particular, there's this trend amongst people to devalue cases of PTSD among criminals, non-military civilians, and sexual assault survivors, often watering their complex rationale down to mere guilt, overreaction/sheltering in an overly politically-correct world, and people being babied on sexual conduct.

There is a severe problem in making the criminal, especially sexual abusers, too sympathetic to where their victims get chewed out for being too hard on somebody. For example, there's Michael Jackson - the recent documentary Leaving Nevermind lays out in great detail how the King of Pop groomed two boys into giving him sexual favors, thus allowing him to do sexual things upon them. I have seen people immediately cancel/disown this guy and resume calling him a monster, albeit with slightly more tact than how we handled the issue back in the '90s - i.e. not making fun of his appearance. People are re-evaluating MJ's second-to-last album HIStory and exposing his own fear of the world's intolerance as immense fear upon receiving his just desserts. Most disturbingly, people are throwing out the belief that Michael acted in his peculiar way because of the immense trauma he received when he was a child by his father Joseph and more or less resuming the idea that he's just this sick mastermind who woke up one day and said "yeah, I wanna take advantage of some kids."

Abusers do not come out of nowhere. They are our product. We create abusers and we have to be responsible as a society for when we empower the abuser too much. Cancelling them or trying to lessen the impact they had upon our cultural landscape is something I'd expect a victim to do - like a victim of sexual abuse similar to the cases detailed in Leaving Neverland - not a passive watcher. Abuse survivors can cancel whoever they want - they are trying to protect themselves from rationale behind why they got abused. They were hurt. Back off of them. Please. But people who merely sympathize with the abused but haven't been abused themselves - that's where it becomes a mix of trying to deny their own part in all of this and performative allyship. You - not the abuse victims of America - want to look good so you don't have to feel guilty about contributing to this toxic cocktail of poisonous ideology. You don't want to admit that your adulation of Finn Wolfhard and Millie Bobby Brown, despite Millie being preyed on by Drake, feeds the same machine that created Drake and Michael Jackson. We propagate extreme youth as a good thing - and as a means to ensure our survival. We make people desire youth to the point where we ingrain it in anybody.

Joseph and Katherine Jackson, Berry Gordy Jr., and America created Michael Jackson by depriving him so hard of a childhood that he felt that the only way to connect with anybody was through being with children at all times. Every time he had to be around an adult, he had to pretend to be an adult. We warped Michael's mind to the point where he thought it was okay to sexually engage with young boys - all because not only did we deprive him of a childhood, we drove within his mind that he had to maintain the youthful ideal by any means necessary.

Jordan Peele seems to be trying to communicate this idea via the characters of Adelaide and Red - that abuse victims are a lot more complex than just "broken butterflies who want to be free" or "total monstrous sickos." The fact that members of the Tethered exhibit recognizably human traits and are revealed to be oppressed people who are trying desperately to rise above should be proof of that. Hell, even the twist concerning Adelaide and Red ties into the idea of abuse victims being more complex - regardless of how you read Adelaide imprisoning Red, Adelaide was still a victim of PTSD from having to experience life in the underground for YEARS. Red was still a victim of Adelaide's.

But there's a problem with connecting such a heavy twist with such a heavy observation - it requires you to have the film spoiled for you (read: the twist ruined) just to decode it properly. It runs the risk of being heavily misread and conveyed in the wrong way if you go into the film blind. And if you don't pick up on the idea of generational and class-driven abuse and the trauma that comes forth in favor of the more prominent ideas about class disparity, the lie of American togetherness, and the sham of big sweeping charities, you can misread Adelaide's problems with PTSD as merely her being guilty over having imprisoned Red for such a long time.

Hell, based on watching the film, it cheapened Adelaide's PTSD in the first two acts and made it look like she was undergoing a really intense guilty conscience for her misdeeds. Her trauma is made phony by proxy of the twist trying to say something about the complexities and circular nature of abuse - because if she's the only who left the Tethered for dead with Red, then what good is she? If Jason can see through her well-kept disguise, then how good is Adelaide? And even if the PTSD is real, even if Adelaide is struggling with her own abuse, doesn't it say something that the film gleefully uses her abuse to comment on how two-faced America is - that it uses her traumatic disorder as a means for cynical commentary?

When you're so cynical of somebody's disability, be it a disorder like PTSD or something given to you from birth like Downs syndrome, you step into woke ableism: where you use disability to comment on a problem in the world and end up cheapening the disability into merely a catch-all symbol for specific societal problems. It's ableism, but in an easy-to-use acceptable package! It's ableism, but it devalues victims and survivors by making them all look like they're the symptoms of some larger problem.

I don't mean to tie in my "society created abusers" point with woke ableism - I was just trying to discuss one of the many, many themes of Us - but I was trying to mention how Peele's devotion to the twist regarding Adelaide and Red inadvertently (or intentionally) cheapens Adelaide's obvious trauma, using PTSD in general as a symbol for America coming to terms with its own reckoning.

Chapter Two: Are We Not Pins?

In 1970, Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale, two students at Kent State University, stumbled upon a tract about devolution. It seemed to be crackpot - instead of evolving, humans seemed to be devolving thanks to media and the thirst for violence by any means necessary - so the two took to making jokes about it, presenting art exhibits and songs about this track that appeared to be dumb in their eyes.

Problem is: Kent State would undergo a horrific tragedy with the death of four students at the hands of Ohio National Guardsmen just a short while later. Mothersbaugh and Casale re-read the pamphlet, hoping to bring some levity to the now-solemn campus, and found that instead of mockery, they agreed with the pamphlet's ideas. Humanity was obviously devolving - if our armed forces were gonna kill random students because other students held an anti-war demonstration on campus (yes, I know the details are a bit more violent than that, but they didn't have to fire on the entire student body as they walked through the promenade, that's just horrible), then what good is humanity with bigger issues like race, gender, sexuality, class, handicap, etc.? Thus was born the band DEVO, the guys in the funny-looking red hats that sang the song about whipping problems away and who led the Ohio art rock scene alongside Tin Huey, Rocket from the Tombs, The Waitresses, Pere Ubu, and Rubber City Rebels. You know - bands you haven't heard of.

Much like Us, I adore Devo's early work. Mothersbaugh and Casale's arrangements are some of the most creative in music, approaching art rock from a more mechanical scene (helping create New Wave entirely by accident - Devo saw themselves more along the lines of bands like Roxy Music than bands like Talking Heads). A lot of their observations are pretty engaging - i.e. the alienation of modern society and industrialization. Their humor is biting but it's appropriately off-beat - "freaks" like Booji Boy are heroic in this fight to recognize devolution whereas conformists like the Smart Patrol have to be taken out in order to make people aware of society's ills. It's great satire with catchy hooks and with enough seriousness in the delivery to not make people laugh too hard to understand what's going on but not take things too seriously. Their first three albums - Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!; Duty Now for the Future; and Freedom of Choice - are some of the finest that art rock and New Wave have to offer, each with their own unique take on the band's sound (Are We Not Men goes for an angular Tin Huey-style rock approach; Duty Now integrates more synths into the songs and experiments with progressive rock; Freedom of Choice mixes both angular rock and synthpop to create the familiar Devo sound we know from early MTV). Check those albums out now.

But be warned: because Mark Mothersbaugh felt that he had to get out the theory of devolution by any means necessary, he took on any symbol he could just to communicate how oppressive society is. Unfortunately, he used a character with Down's syndrome and directly compared his disability with the repetitive nature of the average Joe.

"Mongoloid" (which I'm not censoring because Warner Bros. and Virgin don't, but for sake of not having to use the term over and over because the song title itself is a classic ableist slur for somebody with Down's, it'll be referred to as "That Really Problematic Song Before 'Jocko Homo'" from now on) is about that. On the surface, it's about how somebody with Down's syndrome can live the normal life - they can wear a hat, hold a job, bring home the bacon - so that nobody would notice they were out of the ordinary. But you know why Mothersbaugh used a disabled person to embody the repetitive stupidity of the conformist - it's because a disabled person can't be normal, you know. They're too out of place - but if you give somebody with Down's a pressed suit, a successful business, and enough money to live, they too can contribute to the capitalist nightmare. Also, given the usage of disabled people as catch-alls for the huddled masses of conformed society at the behest of capitalism in the rest of Devo's discography - also look at "Smart Patrol/Mr. DNA" from Duty Now, where dum-dum conformists are labeled as "spud boys" observed intently by the suburban robots that monitor reality (and how "potato" has been used in recent years to refer to mentally-disabled people, especially those who lack acceptable amounts of intelligence) - it's not hard to read anything but a positive affirmation of "we're with you in the fight" that Mothersbaugh has tried to turn the song into in recent years, using it as an audience participation song and cheerleader chant to unite all of the "spud boys" (yes, that's what Devo fans call themselves).

The guy who wrote all the music for Rugrats used Down's syndrome as a cynical means to comment on how we live in a society. Jeez, that's edgy.

But hey, we love it. Devo are commonly regarded as a great band. I still love those first three albums. Hell, I still love "That Really Problematic Song Before 'Jocko Homo'" and "Smart Patrol/Mr. DNA" despite how edgy they are about their usage of the disabled as a catch-all for copy-pasted members of modern society because they're catchy songs with inventive arrangements and some of their best hooks. I understand why people ignore that - most people don't go into Devo's early stuff, but those first two albums are within two years of "Whip It" and "Girl U Want" and all of the songs from the New Traditionalists sessions. They're recent. They're not eight-year-old Tweets some filmmaker did when he was writing that edgy funny video game about the lollipops and the chainsaws that he had to stop and own up to when he got hired to do Doom Patrol, But With Aliens and in Outer Space and with a Raccoon for Marvel. They were songs that Devo performed - and still do - in concert.

Don't cancel Devo. They laid off the "disability = conformist" bullshit back in '82. But Mothersbaugh needs to at least address how people might read that one song from Q: Are We Men? as nothing more than "we live in a society" brought to its limit.

But promise me: if you're gonna listen to some more Devo, please give nu metal another shot.

Why?

Chapter Three: People Hate Nu Metal Because They Hate Abuse Victims (and music critics often have racist biases because something something the fact that so many books something something)

Nu metal is an entire genre that people have decided one day is the absolute worst. That and emo-pop.

Well, there's two nu metal bands that have been rescued from the heap - Deftones and System of a Down. The former got rescued because Internet music geeks really love White Pony while the latter got rescued because Toxicity won all of the Grammys and is therefore important to music. Even then, their early stuff - read: their most emotionally raw stuff - tends to get shoved to the wayside by people who defend their cool-to-love albums. Stuff like Adrenaline and Around the Fur and System of a Down tend to get ignored in favor of albums like Mesmerize/Hypnotize and Koi no Yokan. That's not to say both bands' later albums are any less resonant - Deftones are still at the top of their game even in the wake of Chi Cheng's tragic death and System of a Down are still fighting about whether they should record more Serj solo songs or Scars on Broadway songs.

But still, when they were bands willing to prove themselves, they made their most effective work.

I really don't see why people have decided that nu metal is the worst. I went through my obligatory "nu metal is bad" phase back in late high school/early college before realizing that I like prog rock bands where Peter Gabriel soundalikes scream about lighthouses and conformity while guitar-processed saxophones blare like foghorns and hard rock bands where Eric Bloom and Buck Dharma sing about Lovecraftian horrors in between songs about embracing death and riding planes from World War II. I liked Malkmus' disaffected poetry about being disenchanted with mainstream celebrity AND Mark Farner's wild and shirtless lyrics about partying and living a life of crime. I loved Chino Moreno when he both talked about surrealistic wordscapes AND when he talked about his own experiences as a teenager in Los Angeles - because they come from the same guy. It's still Chino Moreno, even if thought that saying the N-word in "7 Words" was a good idea. It wasn't. It makes him sound corny.

I realized that I actually kinda liked a lot of nu metal. Of course, I held on to the "Limp Bizkit is bad" opinion until really recently, when I decided, just for fun, to listen to the band's third album Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavored Water (i.e. Limp Bizkit Presents Poo-Poo and Pee-Pee because they already told you they were the worst back on Significant Other, did you expect anything else?). And I found it to be...

...pretty good.

There are some glaring flaws with the album - Fred Durst's character of the Truly Oppressed Ultraviolent Rock Star Who Exemplifies Rock Stardom (TM) becomes really grating around maybe "Take a Look Around," where he keeps asking why people hate him for the thousandth time; the album is 75 minutes long when it would be a much better (and more compact) 50-60-minutes long without all the interludes, intro/outros, hidden tracks, and obligatory remixes of "Rollin'" with Redman, Method and DMX cutting a few bars; Durst's humor can get really obvious - but those flaws are outweighed by the strengths. As most Bizkit albums tend to be Durst channeling his upsets through his character alongside the clever arrangements of Wes "That Guy Who Keeps Leaving Limp Bizkit" Borland, Sam Rivers, and John "Actually Lives on the Mathews Bridge" Otto, Chocolate Starfish is a pretty effective capture of what Durst experienced when his band suddenly blew up thanks to the MTV-friendly nature of "Nookie" and "Break Stuff," alongside all the blowback regarding Woodstock '99. When you loudly proclaim that your band is the worst, people start to regard you as such - every person just loathed this band. That was the new trend.

Unfortunately, that included one of Durst and Borland's personal heroes, Trent Reznor. Having the release of his hotly-anticipated follow-up to The Downward Spiral - The Fragile - overshadowed by this overly-aggro band rapping about chainsaws and being mad at your ex, of course you'd be pissed. You put all that time and effort into a song called "Starfuckers, Inc." only for it to get overshadowed by the song whose music video has Limp Bizkit get executed by drowning in milk, only for Fred Durst to lament that Heaven doesn't have that guy from Wu-Tang in it. You'd be pissed - you're one of the few mature artists in the '90s...and you're overshadowed by this puerile band trying to have some fun out of what's essentially an over-the-top break-up album. You say some very choice words about the band's talent, especially their really photogenic and iconic lead singer in the red baseball cap.

You think that "Hot Dog," a song about how they felt burned by you (conveyed in a way only Limp Bizkit can do - and that's by handling the situation transcendentally immaturely), just came out of nowhere?

No, you - the reader - aren't Trent Reznor. Be glad you aren't. That would mean that you haven't made a good album since With Teeth.

But even then, Bizkit - and here's the big shocker - isn't the only band in nu metal. In fact, there are quite a few bands in the genre. A couple of my favorites, i.e. the ones hinted at in that little content warning below the poster, are Deftones and System of a Down, two of the most creative and innovative bands in the mainstream alternative scenes. I know critics will often focus on Neutral Milk Hotel, an excellent band, as the de facto innovative '90s band in the way that they streamlined lo-fi indie production into a very dynamic affair similar to a Brian Wilson album than whatever Robert Pollard recorded during spring break, but NMH and In the Aeroplane Over the Sea tend to get mentioned a bit too much for my tastes. If the critics do decide to go mainstream, it's either an early grunge album, Weezer's Pinkerton, or anything Billy Corgan did - and even then, that's too limiting. And I'm not saying that to rag on these bands - Cobain successfully revived power pop into a viable genre; Cuomo brought new attention to the nascent emo genre by integrating elements with power pop and minor elements of space rock; and Corgan, before he became the absolute worst, about showed people that you could make progressive rock exciting and engaging. Genres that critics considered to have died in the '70s - or at the very least became extremely irrelevant due to changing tastes - and super-niche punk movements in DC and Ohio ended up developing what we know as alternative rock.

Alt-rock is the junk of music, retrieved and made anew with more vigor - nu metal is primarily that as well, albeit with hip-hop and increased funk influences added in for good measure. So why does alt-rock get more love and mu metal not?

Honestly, it has to do with biases. Remember that Milo Stewart video where he said that everybody was racist, even though he said it in the loosest of terms and meant it in the Avenue Q sense - where everybody has some sort of bias against one another that it shapes our own decisions, even when we're not aware of them? I think a lot of the hate behind nu metal is shaped around how a lot of the early practitioners of the genre were women and minorities - because once you strip away Jonathan Davis and Fred Durst from the equation, you're left with a whole melting pot of people. In particular, Deftones are primarily Latino, with the exception of Chi Cheng (Chinese-American), his replacement bassist Sergio Vega (black), and Abe Cunningham (white). System of a Down go one step beyond - they're all Armenian. And guess what they experience on a regular basis? Lots and lots of bigotry driven towards them. Chino Moreno, in particular, experienced police brutality first-hand when he was in his teens - the seven words that "7 Words" refers to are the words in the opening to the Miranda rights. A lot of the stuff on Adrenaline addresses how Chino saw the world as it seemed to act against him.

System of a Down, again, kinda go one step beyond. Being Armenians, a big topic for them is to discuss that one time the Turkish government thought it'd be cool to try to kill every Armenian living in the Ottoman empire in a deliberate manner. Of course, not able to afford a whole bunch of death camps, they relied on death marches and forced army conscription. These actions were prolonged and deliberate, but don't tell the Turkish people (or Cenk Uygur) that - they'll deny that the actions had any genocidal qualities as defined by the Holocaust until the cows come home. But the historical records show that the government promoted and condoned these killings - at this point, if the Armenian Genocide isn't a genocide, then me free-associating about why the ending of Us severely disappointed me and made me think of all the times people write off trauma as either some cool "we live in a society" thing or too whiny for normal people is actually just a review of Avengers: Endgame. Just own up to it, Turkey's government. Call the spade a spade.

When people write off nu metal as some hokey throwaway genre or otherwise act condescending towards it, they engage in this sort of societal denial where people have decided that the pain of millions of Armenians forced to starve to death in the goddamn desert or die for a country that sure doesn't give a shit about them or the pain of minority communities in the US having to deal with cops that can get away with a lot of shit because "they did their jobs right and that's all that counts" or the pain of people betrayed by their idols or the pain of being an abuse victim that isn't believed by their parents because they're think you're faking it...that it's all just somebody trying to be a show-off. Critics of nu metal are less like people who have legitimate qualms with how the genre was marketed to primarily white suburban males and more like Aaron Carter denying that Lou Pearlman severely hurt people even when confronted with the evidence (even evidence from his brother) - they deny trauma because if the trauma turns out to be true, what does that mean for them? What does it mean for Devo that people loudly and proudly calling themselves "spudboys" and singing along to "(insert really long replacement title for that one song about the Downs guy)" at concerts while Mark Mothersbaugh leads them on by chanting the lyrics into a megaphone...often don't have positive attitudes towards the mentally disabled, even among fans who have mental disabilities themselves? What does it mean for Jordan Peele that by making Red into the real Adelaide and Adelaide's PTSD just her feeling extreme guilt over ruining the old Adelaide's life, he's done a lot of potential damage to trauma survivors? It makes them feel bad - to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan from Annie Hall, you mean their whole fallacy is wrong. Of course, "fallacy" being McLuhan and Woody Allen forgetting about the term "philosophy" for a hot minute.

To those creators, if anybody can point out an unintended effect of something they've been working hard to get out, then the something in question is dead in the water. Some creators just ignore it because - here's another shocker - nothing is perfect. Everything - and I mean everything - is problematic. It's all rooted in their modern times, not ours. Nothing ages gracefully - and it's not supposed to. The best art is the current art that impacts us the hardest - and yes, that includes superhero movies - alongside older works that either don't start to become relevant until the future or works that age slower than most works. If creators just embraced this, then maybe they'd be more willing to listen to the concerns of fans and critics who want nothing but the best for them, but don't think that everything Mark Mothersbaugh made is perfect and god-like. But instead, creators opt to just ignore these questions - after all, ignorance is bliss, so forget that Devo and Jordan Peele and critics of nu metal often use ableist tropes in different ways to get out the message that society is sick, the class disparity problem in America is something we need to fix NOW, and that marketing Korn and Limp Bizkit exclusively to white male audiences will create some bad disconnect and stigma for an otherwise super-diverse genre. We just remember their messages.

Or at least that's the intent.

But even then, Bizkit - and here's the big shocker - isn't the only band in nu metal. In fact, there are quite a few bands in the genre. A couple of my favorites, i.e. the ones hinted at in that little content warning below the poster, are Deftones and System of a Down, two of the most creative and innovative bands in the mainstream alternative scenes. I know critics will often focus on Neutral Milk Hotel, an excellent band, as the de facto innovative '90s band in the way that they streamlined lo-fi indie production into a very dynamic affair similar to a Brian Wilson album than whatever Robert Pollard recorded during spring break, but NMH and In the Aeroplane Over the Sea tend to get mentioned a bit too much for my tastes. If the critics do decide to go mainstream, it's either an early grunge album, Weezer's Pinkerton, or anything Billy Corgan did - and even then, that's too limiting. And I'm not saying that to rag on these bands - Cobain successfully revived power pop into a viable genre; Cuomo brought new attention to the nascent emo genre by integrating elements with power pop and minor elements of space rock; and Corgan, before he became the absolute worst, about showed people that you could make progressive rock exciting and engaging. Genres that critics considered to have died in the '70s - or at the very least became extremely irrelevant due to changing tastes - and super-niche punk movements in DC and Ohio ended up developing what we know as alternative rock.

Alt-rock is the junk of music, retrieved and made anew with more vigor - nu metal is primarily that as well, albeit with hip-hop and increased funk influences added in for good measure. So why does alt-rock get more love and mu metal not?

Honestly, it has to do with biases. Remember that Milo Stewart video where he said that everybody was racist, even though he said it in the loosest of terms and meant it in the Avenue Q sense - where everybody has some sort of bias against one another that it shapes our own decisions, even when we're not aware of them? I think a lot of the hate behind nu metal is shaped around how a lot of the early practitioners of the genre were women and minorities - because once you strip away Jonathan Davis and Fred Durst from the equation, you're left with a whole melting pot of people. In particular, Deftones are primarily Latino, with the exception of Chi Cheng (Chinese-American), his replacement bassist Sergio Vega (black), and Abe Cunningham (white). System of a Down go one step beyond - they're all Armenian. And guess what they experience on a regular basis? Lots and lots of bigotry driven towards them. Chino Moreno, in particular, experienced police brutality first-hand when he was in his teens - the seven words that "7 Words" refers to are the words in the opening to the Miranda rights. A lot of the stuff on Adrenaline addresses how Chino saw the world as it seemed to act against him.

System of a Down, again, kinda go one step beyond. Being Armenians, a big topic for them is to discuss that one time the Turkish government thought it'd be cool to try to kill every Armenian living in the Ottoman empire in a deliberate manner. Of course, not able to afford a whole bunch of death camps, they relied on death marches and forced army conscription. These actions were prolonged and deliberate, but don't tell the Turkish people (or Cenk Uygur) that - they'll deny that the actions had any genocidal qualities as defined by the Holocaust until the cows come home. But the historical records show that the government promoted and condoned these killings - at this point, if the Armenian Genocide isn't a genocide, then me free-associating about why the ending of Us severely disappointed me and made me think of all the times people write off trauma as either some cool "we live in a society" thing or too whiny for normal people is actually just a review of Avengers: Endgame. Just own up to it, Turkey's government. Call the spade a spade.

When people write off nu metal as some hokey throwaway genre or otherwise act condescending towards it, they engage in this sort of societal denial where people have decided that the pain of millions of Armenians forced to starve to death in the goddamn desert or die for a country that sure doesn't give a shit about them or the pain of minority communities in the US having to deal with cops that can get away with a lot of shit because "they did their jobs right and that's all that counts" or the pain of people betrayed by their idols or the pain of being an abuse victim that isn't believed by their parents because they're think you're faking it...that it's all just somebody trying to be a show-off. Critics of nu metal are less like people who have legitimate qualms with how the genre was marketed to primarily white suburban males and more like Aaron Carter denying that Lou Pearlman severely hurt people even when confronted with the evidence (even evidence from his brother) - they deny trauma because if the trauma turns out to be true, what does that mean for them? What does it mean for Devo that people loudly and proudly calling themselves "spudboys" and singing along to "(insert really long replacement title for that one song about the Downs guy)" at concerts while Mark Mothersbaugh leads them on by chanting the lyrics into a megaphone...often don't have positive attitudes towards the mentally disabled, even among fans who have mental disabilities themselves? What does it mean for Jordan Peele that by making Red into the real Adelaide and Adelaide's PTSD just her feeling extreme guilt over ruining the old Adelaide's life, he's done a lot of potential damage to trauma survivors? It makes them feel bad - to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan from Annie Hall, you mean their whole fallacy is wrong. Of course, "fallacy" being McLuhan and Woody Allen forgetting about the term "philosophy" for a hot minute.

To those creators, if anybody can point out an unintended effect of something they've been working hard to get out, then the something in question is dead in the water. Some creators just ignore it because - here's another shocker - nothing is perfect. Everything - and I mean everything - is problematic. It's all rooted in their modern times, not ours. Nothing ages gracefully - and it's not supposed to. The best art is the current art that impacts us the hardest - and yes, that includes superhero movies - alongside older works that either don't start to become relevant until the future or works that age slower than most works. If creators just embraced this, then maybe they'd be more willing to listen to the concerns of fans and critics who want nothing but the best for them, but don't think that everything Mark Mothersbaugh made is perfect and god-like. But instead, creators opt to just ignore these questions - after all, ignorance is bliss, so forget that Devo and Jordan Peele and critics of nu metal often use ableist tropes in different ways to get out the message that society is sick, the class disparity problem in America is something we need to fix NOW, and that marketing Korn and Limp Bizkit exclusively to white male audiences will create some bad disconnect and stigma for an otherwise super-diverse genre. We just remember their messages.

Or at least that's the intent.

Chapter Four: So What Do We Do Now?

The easiest step would be to promote an air of self-awareness regarding the messages the creators put out there. Like, if Devo would admit to the intense ableism of their first three albums - again, really great albums, I must stress - or Jordan Peele admitted to how the final twist in Us can be read as a justification for doubting the legitimate trauma of people, then we'd probably have precedent to improving their works. However, in regards to how critics reacted to nu metal, critics are critics - you'd have to give them entirely new information to make them reanalyze the things they've said. You'd have to give, say, Anthony Fantano or Crash Thompson enough reason to doubt why they've been ragging on Fred Durst for years - or why post-rock fans rag on Frank Delgado for not making the right soundscapes with his keyboard/turntable set-up. I'm not the right person to give Crash or Melonhead that necessary information - nu metal didn't click for me as well as others. I just started listening to it in 2007 because it felt heavier than most music on the radio. Sure, it felt like it was stepping back into 1999, but nu metal felt heavier. When I became aware of the lyrics, I began to question why I liked the genre in the first place.

All I can say is that I stuck it out with the genre. Yes, I knew that Limp Bizkit was not a cool band to like even in 2011-12, but I personally didn't mind when somebody played "Break Stuff" in the car because, to those people, it's a fun song to get out some aggression to.

But even then, that's not enough. I began to look at how other people approached nu metal - why the fans still attach themselves to it, as evidenced by some of the most heart-wrenching (read: not serial harassers) comments you'll ever see on a YouTube page. These people are attached to the music not because it fooled them into thinking that it was good but because it helped them through some hard times. I can relate to that. I have some staples in my music taste that came about because I listened to them just to keep sane during some pretty confusing times. Bands like Split Enz, Motorpsycho, Silverchair, Death Grips, Cardiacs, Van der Graaf Generator, Supertramp, Boredoms, etc. - all of those bands I got into when the going got rough. I don't want to give specifics, but during those times that I got into those bands, I felt like the entire world was against me. The only music that made sense to me at the time was oddball music. Australian prog-folk bands with weird costuming and even weirder stage antics, Norwegian alt-rock bands with psych and prog influences, Australian post-grunge bands with a penchant for the orchestral and the quirky, heated new bands from Sacramento cutting their teeth with one of the most powerful mixtapes ever released, oddballs from Kingston upon Thames who mix neo-prog pomp with hardcore punk speeds, art school weirdos who eschew guitars for two saxophones played by one person, more art school weirdos who write pop songs cleverly disguised as prog symphonies, and actual people who worship the actual sun - that's the kind of music that about described my dark periods. The outcasts, the weirdos, the Norwegian alt-rock bands that couldn't get signed in the USA despite having the backing of one of the biggest music companies in the world - those told me that everything was gonna be alright. Everything was gonna be in its right place in the end.

Nu metal was the same as well. I guess it just clicked on many a car ride. But ever since it clicked, I felt like I've had to defend the genre and try to prove to people that it's a lot more than Dez Fafara screaming about being loco while Ozzy in a Good Humor uniform duct-tapes a View-Finder on his head. No, it's about dealing with your trauma. It's about making do with what society gave you - and telling society that you won't be pushed down any longer. It's a lot more profane - and let's not get started on how edgy a lot of these bands were - but it certainly feels more productive than Devo bringing to mind my cousin when talking about cogs in the machine or Jordan Peele stating that trauma is just perverted guilt by those who rightfully feel guilty. Nu metal is about triumph over the odds - it's about preventing the bad things from happening again - and it's about coming to terms with your trauma. It uses trauma constructively, unlike what Peele might tell you with those final six minutes of Us.

Maybe I am stuck in the Sunken Place. Maybe I'm not enlightened enough to accept Us for what it is - because I have to stress this again: the rest of the movie is really damn good. But as Anita Sarkeesian once said, "It's both possible - and even necessary - to simultaneously enjoy media while also being critical of its more problematic or pernicious aspects." And if I have to delude myself into thinking that my favorite things are totally pure and aren't of ill repute in some sense, then what good is media? What good is criticism if people equate pointing out the boo-boos or missteps in something with outright censorship? Nothing is perfect. Nothing will be.

Let me put it like this: if Jim DeRogatis can hate Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band while being generally receptive to other Beatles albums, then I can think that Us has some really bad choices made in the ending while still thinking it's a good movie. Hell, going back to that greater good essay I wrote back in September, I still love the hell out of Zootopia even though I think it doesn't do enough to showcase how deep a lot of police brutality and societal biases go. It instead gave us the easy answer - the system's problems can all be blamed on Bellwether. But how good is the answer if it's that simple? Why is Bellwether evil? Why does she feel the need to exploit the psychosomatic effects of the Night Howler in order to get her way? What led her to go down this path? By making Ade's PTSD just some roundabout guilt for her crushing Red's larynx and trapping her in the underground back in 1986, Us gives us the easiest answer: everybody is complicit in the system. But the harder answer would be to discuss how everybody is complicit, how trauma survivors and victims can help stoke the flames of class disparity and otherism even when they aren't aware of it - and it wouldn't be by invalidating Ade's trauma as a character and having her own son put on his mask because he knows that his mom is the real Tethered.

You could pull some Thermian argument and say that Bellwether was bullied by Mayor Lionheart to the point of breaking - or that Ade was always some sort of disingenuous about her origins with her above-ground family - but what good is that? Those just create more pernicious implications. Bellwether being bullied into being a vigilante for her own racist cause kinda reminds me of all the people who still insist to this very day that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold wouldn't have shot up Columbine High if they weren't relentlessly bullied.

I was relentlessly bullied in middle school. Somewhat so in high school. Hell, I was bulled on the Internet by people that I thought I could trust - I still have trauma from those situations. But you wanna know the difference between me and Eric and Dylan? I didn't kill people just to get revenge on people. I didn't become a totally disingenuous person just to make people think that I had actual PTSD.

Humans are a lot better than people give them credit for, Mr. Peele. Don't settle for the easy answers anymore.

Comments

Post a Comment